Show your work.

Many a math teacher has uttered this 3-word phrase. Can you demonstrate evidence to back up your results? Doing the calculations in your head to get the correct answer doesn’t assure you will be rewarded with a 100% passing grade. It’s often a matter of being able to decipher precisely HOW you arrived at an answer that determines whether a teacher feels confident that you understand the logical progression of working through the steps in the mathematical process. Can you justify your answers with reason and demonstrate your process in a way that enables a fellow student of the same material to understand and follow your lead?

It’s been nearly 20 years since I graduated high school, and while I’ve heard complaints and resistance to the trend of Common Core math becoming the standard in elementary schools for years, I’m only just recently beginning to explore how I personally feel about this educational approach. My daughter is in an advanced math class in 2nd grade, and sometimes her homework looks like a complex pictogram with all sorts of arrays and circles and long drawn out numbers and place values that I don’t remember using when learning basic arithmetic.

I’m not prepared to argue for or against the Common Core math approach in this post other than to say that I believe there is not a one size fits all approach to learning, and intelligence isn’t necessarily measured by test grades. We all have different strengths and weaknesses, and this variety is essential to our ability to approach and solve problems from a wide range of perspectives. Verbal ability varies. While I think it is helpful to develop skills to reason and defend answers, specific supporting evidence can look very different across the spectrum of uniqueness. An autistic child may have superior abilities to quickly calculate numbers but have difficulty verbalizing how the connections are made. Likewise, some students are frustrated by tedious requirements to diagram lengthy explanations for simple problems, while other more abstract thinkers benefit from taking extra time to visually make sense of the reasoning behind solving an equation before attempting to manipulate the numbers.

Beyond math applications, show your work is a phrase I’ve been repeating to myself often in recent weeks as I experiment with new approaches to record keeping, personal progress analysis, and clear communication.

I have a tendency to keep a lot of things in my head that never get written down or even spoken. Verbalizing my feelings or arguing my position out loud in conversation has not been something I’ve typically identified as a personal strength. I tend to be quiet and contemplative, and I observe and internalize many things that aren’t readily apparent to the average onlooker or even close companions for that matter. While there is value in introspection, writing out my thoughts helps clarify and solidify my point of view and also creates a basis for touchpoints in conversations with others; thus, writing is a practice I’m attempting to utilize more often when communicating boundaries and expectations as well as processing thoughts and feelings.

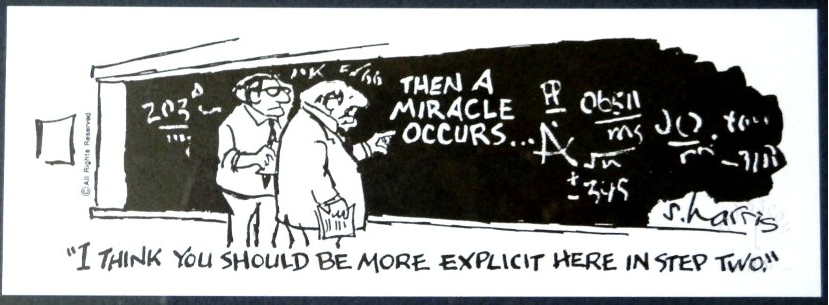

Conversations, whether written or auditory, allow us to get feedback on our work. Often, we can benefit from being open to objective opinions from outsiders, who can look at a problem and our attempts to solve it one way and then give us insights on a completely different approach. Thus, there is great value to be had in cultivating conversations and embracing constructive criticism. It’s easier to see the mistakes in someone else’s argument than to identify the inconsistencies in your own; it’s not easy to change your own mind and consider that you may have to back up and start again from a different approach, but a nudge from an outside source may be the very thing that causes you to clarify your constructs. Don’t be afraid to blow holes in your own proofs; finding and filling in gaps makes the foundation stronger.

Show your work is also a cognitive tool to capture and document details that are prone to be forgotten; list making and note taking are great places to start.

Our brains have limited active working memory or bandwidth, and the more we can highlight and record our thoughts externally, the more we can free up our cognitive capacity for greater comprehension and creativity. Recall can be aided by cultivating habits of documentation, whether that be list making, journaling, highlighting, note jotting, photo snapping, or soundbite clipping – and then organizing it all in a usable way.

For instance, I’ve read many books over my lifetime, but I know there has been a great deal of information that seemed relevant and inspiring at the time yet has since faded from memory. I’d be hard pressed to give a synopsis of many books I read 10 years ago; I don’t remember the titles of every book I’ve consumed, and sometimes I look over book covers and summaries and can’t even remember if I actually read them or not. I’ve gone through some phases of life where I read a great deal, and other times where books are a minimal consideration for years on end. Recently, I’ve gotten back into a habit of reading portions of books nearly every day, and I’m exploring different methods to improve retention of the information I’m learning.

Even though I’ve used Evernote’s cloud-based app off and on for 8 years to organize information, in recent weeks I’ve been integrating these digital notes and notebooks in my regular workflow to a degree that far surpasses my previous usage. I’m collecting ideas as I they come to me alongside links and clips from articles I want to reference and review later. One of the next experiments I want to try in Evernote is to keep a running log of key quotes and takeaways throughout the process of reading a book.

Speaking of key quotes in books, another new (to me) example of show your work I’ve started to do in recent weeks is to read physical print books with a pen nearby, and actively underline and notate passages that particularly strike me as significant. I have always kept my books pristine and didn’t think anything of the difference of reading a library book vs. owning a book beyond the cost, anticipated duration to read, and long-term storage space. Even with school textbooks, I was never one to write or highlight — but let me tell you how liberating it feels to start scribbling notes and stars in the margins after all these years! It’s also far easier to go back and locate key ideas when reflecting on the material, and taking action while reading makes the information stick in your head so much better.

I know some people find it preferable and more efficient to digitally highlight Kindle books and then export those notes to Evernote; I see the value in both, though currently I prefer to have a physical book in hand as an excuse to detach from screens. However, I do also like having an ongoing Kindle book to read, as sometimes I find myself places such as a park while my daughter plays where I only have my phone in hand but don’t want to spend all my screen time scrolling social media. The format of the book Tools of the Titans by Tim Ferriss was particularly good for bite size consumption on a screen, though I’m seriously considering buying a physical copy of the book to keep on hand for easier reference.

I’ve adopted show your work as a personal mantra of late to reinforce new habits and practices of writing and documentation with the intention of reviewing on a consistent basis.

Doing this requires some pretty significant shifts in how I structure my time and processes of learning, planning, and reflecting. I have a goal to establish a habitual routine of regularly reviewing my notes and adjusting focus as necessary, which includes weekly and monthly planning sessions to analyze progress, intentions, and schedules for business and personal projects. I also want to keep a running monthly log of measurable steps completed towards yearly goals and strategically conduct year-end reviews – which all requires diligence in recording notes in real time and organizing that work in ways that can be quickly referenced later.

This is expansive new territory for me, as about the most I’ve done of this sort of thing in the past (beyond monthly and yearly financial business accounting) has consisted of saving new albums I’m digging on Spotify and publishing my top 10 albums list in 2017 and 2018. I could still go back and pull together a top album list for 2019 pretty easily, but my time was far more focused on laying a foundation for this blog and setting future goals and plans in the final weeks of December 2019 that the music roundup took a backseat. Instead, for the first time I created a list of books read going back 3-4 years, plus some key influential titles from years prior to that. This task wasn’t particularly hard as the 6 books I read in the 4th quarter of 2019 were comparable to the total books I’d read in the previous 2-3 years combined, but now that the bones of my book list exist, it will be that much easier to keep a running reference log over time.

Show your work in the form of progress monitoring is eye opening and great for perspective and motivation.

You are more likely to manage what you measure. If you want to implement behavior changes, track improvements, or minimize repeat mistakes, then try keeping a written record and refer to it often. The increased focus and attention that occurs when you write something down, review it regularly, and respond accordingly can create a powerful force for change. This practice can take the form of habit tracking, goal checklists, question queues, and mistake logs.

This level of documentation is also a new practice that I’ve been exploring in various forms in recent months. It started with learning about the idea of keeping a mistake log via Robert Glazer while I was in the midst of a new work project where I was learning all sorts of things in the span of a few short weeks of tight deadlines, some by trial and error. I compiled a list of mistakes to learn from at the end of the 6-week project and shared it with my manager for the sake of transparency and accountability. The missteps weren’t necessarily serious from a big picture view, but several would be time and/or resource wasters if repeated.

That experience bled right into reading The Happiness Project by Gretchen Rubin, which I serendipitously picked up at a thrift store having no idea how much it would inspire me to take action on mapping out plans for monthly and yearly goals and tracking behavior changes to the point of deciding to create the year-long 2020 Math Project for myself – even though at first the idea of her devotion to daily spreadsheets and extreme level of organization seemed way too Type A for me.

The more I study habits and the science of behavior change, however, the more sense it makes to visually track certain behaviors, as it puts things into perspective when you can look back at a month for example and see how frequently you exercised or ate healthy or kept your temper in check or took steps toward achieving a long term goal. James Clear makes a convincing case for habit tracking in his excellent book Atomic Habits – so much so that I bought the companion journal as way to experiment with habit tracking and plan on starting next month with a focus on 2020 habits: my first behavior change experiment is a goal of 20 minutes of intentional movement (like walking or stretching) for at least 20 days out of the month.

I’m also starting to record questions as they arise so I can remember to seek out the answers sooner rather than later – particularly in the context of work, as lately I’ve been tasked with several new projects that are expanding my knowledge while demanding consistency within standards of which I am just becoming familiar. As I learn new software and get oriented on a new company’s protocol while also often working independently from a remote location, I can comb through my notes and outline a concise list of questions to address in future meetings with supervisors and teammates. This work-flow organization promotes efficiency, accuracy, and accountability, and helps me stay on track by sharpening my focus and distilling my queries to prioritize key areas of focus.

Show your work does not necessarily mean you have to share your work publicly.

It can strictly be a private system of documenting your process. It could take the form of lengthy journal entries, or a one sentence reflection of gratitude at day’s end. The key idea is to identify something you can record in a way that you can reflect back on later. Maybe words flow easily when you speak? That’s not the case for me, but you might benefit from recording audio notes and then replaying or transcribing the words. The technologies we carry in our pockets these days makes it easy to find a system that works for you.

It could also be a photograph or sketch – plenty of early bloggers transitioned in recent years to keeping their diaries on Instagram. Experiment with whatever resonates with you; the method does not have to be verbal. Maybe filming a documentary v-log and publishing on a YouTube channel is more your jam? It’s cathartic to get ideas out of your head. A commitment to regular digital documentation is not a new idea; many people intentionally snap a photo a day or make some other daily or weekly commitment to action and output. Social media and blogs support this sort of journaling, though I want to reiterate that public display isn’t necessary: you can still take advantage of the ease of use of online platforms while controlling privacy settings to match your comfort level. Public sharing adds another level of accountability to showing your work; you have to decide if that is a motivator or a detractor.

For me personally, I feel compelled to share my lessons learned alongside new insights for growth and change publicly on my blog this year as a way of documenting my journey and turning frustrations and failures into seeds of success. If I can help others learn from my mistakes, as well as reflect on my choices and consequences in hopes that I can break or reinforce certain cycles and patterns of behavior in my own life, then I’m contributing to making the world a better place. Hopefully I can help others avoid some of the mistakes I’ve made. Wisdom comes from experience, but reflection does no good if you don’t use it to create future change.

If any of these ideas inspires you to show your work, or if you have already cultivated a practice of showing your work, I’d love to hear about it via the comments below or use the hashtag #2020MathProject. If you want to try out your own version of a 2020 habit challenge (maybe 20 days of journaling, meditating, or practicing a new instrument next month?), you can learn more about James Clear’s approach to habit tracking here.

Sharpen your pencils and get to work!

“And then a miracle occurred” comic by Sidney Harris – www.sciencecartoonsplus.com